Proactive Power: A Deep Dive into Restructuring Antecedent Conditions

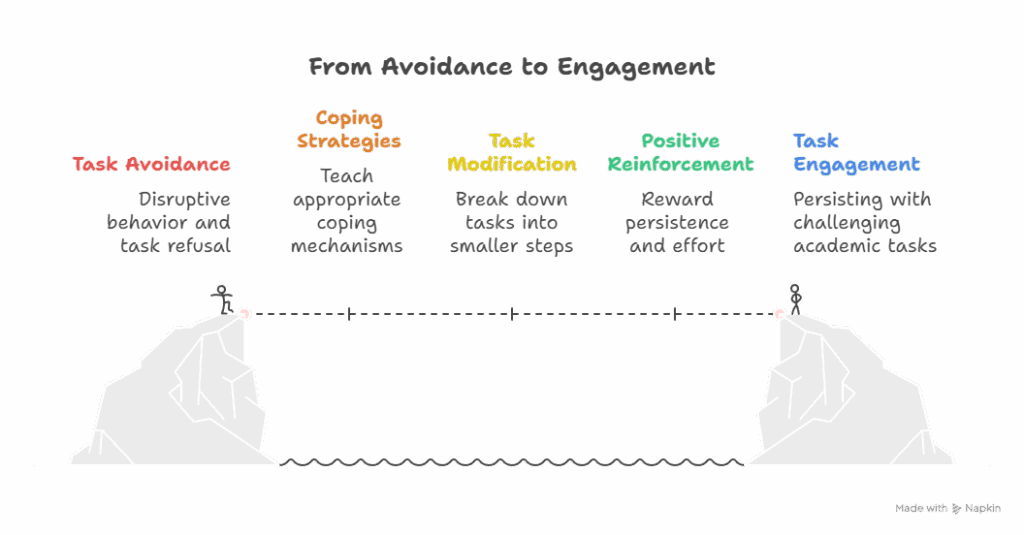

As a behavior interventionist, one of the most powerful tools in your toolkit is the ability to be proactive. Instead of just reacting to challenging behaviors, we can strategically shape the environment to prevent them from happening in the first place. This is the core of restructuring antecedent conditions. By modifying the environment or the task itself, we set our students up for success and reduce the need for them to engage in problem behaviors.

Let’s break down four highly effective antecedent strategies you can implement in a school setting.

1. Modify Academic Requirements

This strategy is all about making overwhelming tasks feel manageable. For many students, a full page of math problems or a multi-paragraph writing prompt can trigger immediate anxiety and avoidance. By breaking the task down, you lower that initial barrier to starting.

- Why it works: This approach, often called “task analysis” or “chunking,” reduces the cognitive load on the student. Instead of facing one large, intimidating task, they face a series of small, achievable steps. Each completed step provides an opportunity for success and positive reinforcement, which builds behavioral momentum and confidence.

- Implementation in the Classroom:

- Math Worksheets: Use a blank piece of paper to cover all problems except the one the student is currently working on. As they complete each one, reveal the next.

- Writing Assignments: Instead of saying “write a story,” break it down into a visual checklist: 1) Brainstorm three characters. 2) Choose a setting. 3) Write the first sentence. 4) Write the next three sentences. This makes the process concrete and less abstract.

- Reading: For long passages, place a sticky note after each paragraph. The goal is simply to “read to the sticky note,” then take a brief pause or check for understanding before moving on.

2. Provide Limited Choices

Offering choices is a simple way to increase student buy-in and cooperation by giving them a sense of control over their learning. When students feel they have some autonomy, power struggles often decrease, and engagement naturally increases.

- Why it works: This strategy taps into a fundamental human need for autonomy. By providing simple, acceptable choices, you are sharing control with the student. This validates their voice and makes them an active participant in the task rather than a passive recipient of a demand.

- Implementation in the Classroom:

- Order of Tasks: “We have a math worksheet and spelling practice. Which one do you want to do first?”

- Materials: “Would you like to write your answers with a blue pen or a black pen?”

- Location: “Do you want to work on this at your desk or at the quiet table in the back?”

- Key Consideration: The choices should always lead to the same outcome. The option is not if they do the work, but how, where, or in what order they do it.

3. Use Strengths and Interests Often

This is the art of making learning relevant and motivating. When we connect academic tasks to something a student is genuinely passionate about, their willingness to participate can skyrocket.

- Why it works: From a behavioral perspective, this is a form of pairing. You are linking a neutral or less-preferred activity (like a math worksheet) with a highly-preferred stimulus (like their favorite video game). This pairing can make the academic task itself more reinforcing and enjoyable over time.

- Implementation in the Classroom:

- Math Word Problems: Tailor problems to the student’s interests. For a student who loves basketball: “If LeBron James scores 8 three-point shots and 5 two-point shots, how many points did he score in total?”

- Reading and Writing: Use books, articles, or writing prompts about their favorite topics, whether it’s dinosaurs, space exploration, or a popular YouTuber.

- Reinforcement: The activity itself can become a form of reinforcement. “As soon as you finish these five spelling words, you can draw a picture of your favorite Pokémon.”

4. Allow the Student to Appropriately Escape a Task/Situation

Many challenging behaviors serve one primary function: to escape or avoid a difficult task. Instead of fighting this, we can teach a student a more appropriate and functional way to get that need met. This is a foundational concept in Functional Communication Training (FCT).

- Why it works: This strategy teaches a replacement behavior. You are providing the student with a simple, low-effort communication skill (like handing over a card) that achieves the same result as the more challenging behavior (like flipping a desk). When the student learns that the new, appropriate skill works more efficiently than the old behavior, they will begin to use it instead.

- Implementation in the Classroom:

- Break Cards: Give the student a small, laminated card that says “Break.” Teach them that when they feel overwhelmed, they can place the card on their desk to request a short, pre-determined break (e.g., 2 minutes).

- Verbal Phrases: Teach a simple, scripted phrase like, “I need a minute, please.”

- Consistency is Key: For this to work, you must honor the request immediately and consistently, especially when you first introduce the system. This builds trust and proves to the student that the replacement behavior is effective. The break should be structured—it’s not free time, but a short, quiet moment to reset before returning to the task.